“You’re very brave” “Mummy, have you SEEN where Jordan is?” – accompanied by dragging me to look at the world map in the play room “I don’t think I could do it..”

All things that I heard in the fortnight before I left the Isle of Skye to travel to Jordan with the charity World Vision to meet just a few of the 630,000 Syrians who have fled from the war and destruction at home and have been given sanctuary in Jordan. I shrugged off what people said. Jordan is perfectly safe, there is no threat from the refugees… but as I fly over Israel at night on our descent into Jordan and look at the seat back flight path monitor all too familiar names come into view Damascus, Homs, Aleppo, Al Raqqa… I don’t feel quite sure..

I’m travelling with Kate and Steph from the World Vision office in London, Elias from World Vision in Jordan (an office of around 70 with additional field workers) and our driver for the week is Saddam. The traffic in Amman and on the pretty appalling roads once we head out of town mean that we are very glad of his skills.

On Monday morning we head north to Irbid, about 20km south of the Syrian border and now home to many Syrian refugees. Our first visit is to a remedial school for boys attended by both Jordanian and Syrian children. Although schools are on holiday across Jordan this week, the classrooms are full here.

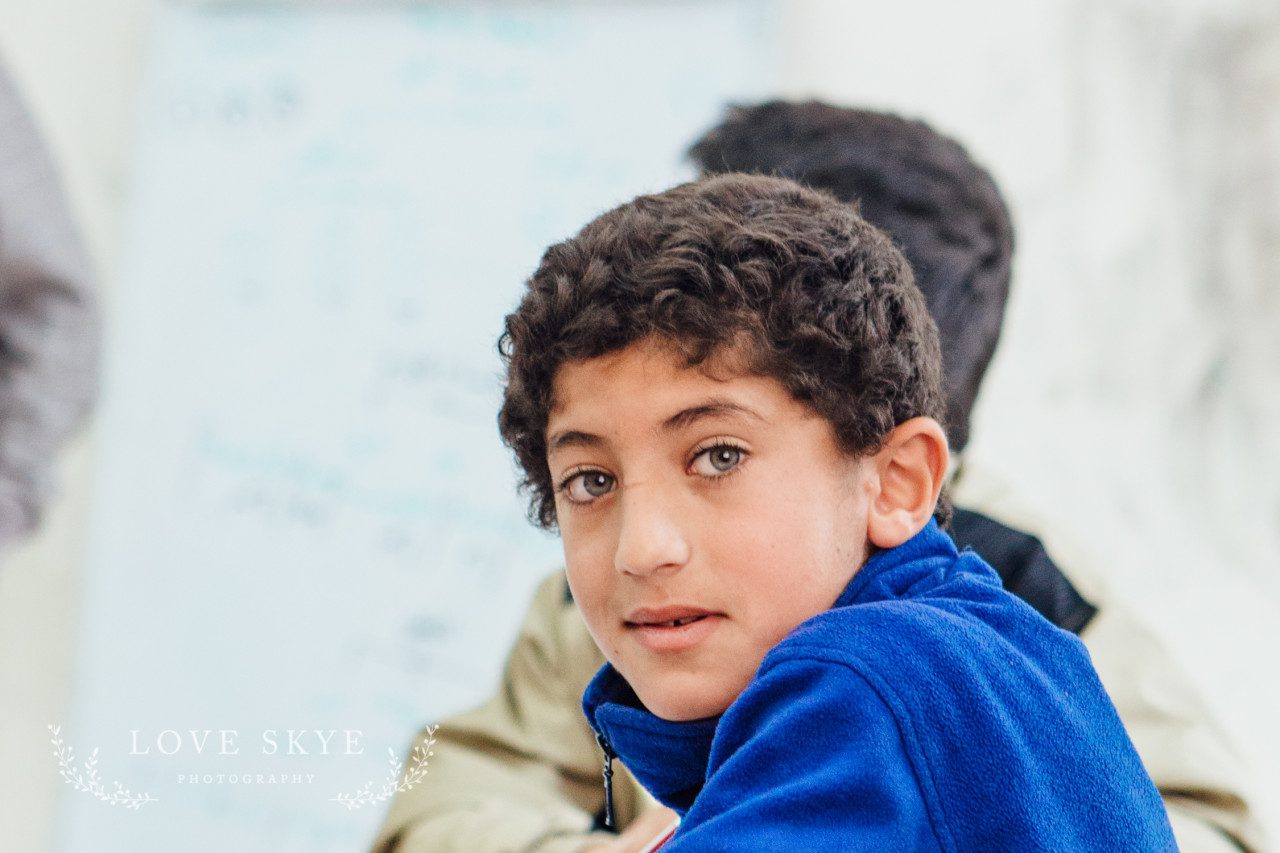

Around me a sea of quiet children, seated in rows of desks, heads bent over paper and pencil. It isn’t long until curious eyes peek up from under dark lashes and the odd shy smile emerges. As I smile back and raise my camera the children throw caution to the wind and rise from their desks and fling their arms around their friends for me to take a class photograph. Seconds after that they cluster round me to look at the back of my camera and to smile and point each other out to their friends. “Good photo” says one of the boldest. “What’s your name?”

It could be any class, any where. But of course it’s not. Half of these boys had experienced real terror, fleeing for their lives and seeing violence and feeling loss that is hard for us to understand. We wander around looking at the pupils work, talking with their teachers. “The children are always excited to be at school” says one teacher. I ask the boys if they like school. “No,” one giggles, “we like playing football” but he is just teasing. Their pleasure at simply being there is evident. At snack time the school provides a hearty sandwich and juice – breakfast for many of the boys – and we chat with the teachers about the challenges of their job. One boy, Abdullah, proudly produces a hand full of glass marbles from his jacket pocket. They have very little but they want to share it with us. The school operates almost without resources – the motivation of both students and teachers is overwhelming. No books, no screens, no learning aids. Board, pen. Paper and pencil.

After school, Abdullah takes us to meet his family.

We are greeted at the door by warm handshakes and kisses by his Mum Entisar. In a 3 room basement apartment in an unfinished building nearby to the school lives a family of 9. It is less crowded now that the father’s parents have returned to Syria. The apartment is cold and a little damp. But it is safe. There is shelter, water, electricity and on the sum of £15 per head per month the family clothes, feeds and educates their children. £15 per month per head. A frozen chicken costs £3. Food is mainly potoatoes and breads. There is no money for health care nor anything but the most basics of life. There are no possessions.

Possessions were left behind when the family home was shelled 4 years ago and they fled into a snowy night. Everywhere they ran to “the slaughter started again”. Eventually the mother found a driver to take them across the border. They had to pay extra as her mother in law is in a wheelchair. On arriving in Jordan they went first to Za’atri camp, but as some of the children had shrapnel injuries they were moved to this apartment.

The youngest 3 children have no memories of Syria, and their 18 month old daughter was born in Jordan. They foresee no return. The eldest son (20) moves around us often with glasses of sweet hot tea, he shows us his school certificates. He was studying pharmacy, but continuing those studies seems a dream now. He clings to hope that one day he will get a phone call approving him for re-settlement in Europe “anywhere I can study”. I nod, but I as I think of the odds of that call coming I choke back tears. The children’s father, Rasheed, comes into the guest room where we are seated with the children and their Mum and tells us that he and his wife had very little education. They came from Daraa, just across the border. It is a farming area, people’s lives are simple. Education is respected. It was all they hoped for, for their children. And there is time now for these youngest children. The hospitality we are given is so warm and enveloping. There is a great openness about the family story. Sometimes there are tears and frustration but for the most part they explain their new situation plainly, without adornment. Just like their new lives. On leaving Entisar leaps up and says she forgot to give us something, (we have already drunk coffee and tea and said we can’t possibly stay for lunch). She hands each of her 6 guests a Twix bar. I am completely humbled.

Later that night I phone my children to tell them that I am bringing them home a very special chocolate treat and they cry when I tell them the story. The twix is sitting on my desk as I write and the room is scented with the perfume of a handmade soap that I was given in another home. Time and again we were given so much by those with so little.

The next day we head north again to meet two more families who are living in host communities. We are greeted by a local team from World Vision who take us to meet the families in their apartments.

It’s hard to write about the first family we meet. Their apartment is bare and cold although the weather is mild. They are clearly struggling. They have come from Homs. Scenes of horrific destruction. We fled they said and everywhere we went the slaughter continued. The older children in the family are out, picking up what ever unofficial work they can to contribute to the family budget. Their 9 year old boy has what appears to severe autism with very limited communication and his Mum has mental health problems. They share the same medication (perhaps tranquilisers) that they can buy from a Syrian doctor nearby. They know they are struggling, they have relatives nearby who are much better off but who will not or cannot help. This little family has become isolated in their new country. They only want to go back to Syria. Life is so much worse. Before the men had work and the children could concentrate on their education. They had access to the healthcare that they simply cannot afford in Jordan.Yet there is no expressed bitterness, no anger. Just a feeling of sadness of how life has turned for them. But even in the midst of this there are moments of smiles.

I sit on the floor with the two youngest children. We have brought a bag of sweets and they gleefully shovel them into their pockets, then they bring them back out to offer to share with me and teach me how to count out their piles of treasure. 15 sweets each! They love having their photographs taken. Their bare feet are cold but they don’t seem to notice. As we pile outside to say our goodbyes they slip on flipflops.

We went to visit another family nearby. Here friend ship was everywhere and everything that sustains them. From the Daraa region they were also forced to flee. But they did not come alone. The highly engaging patriarch of the family Feras, who is 70, introduced us to one of his neighbours who joined us for coffee. His neighbour, Ibrahim, is 75 and they have been friends since their primary school days. “We went to each others houses – all the time – we had sleepovers” and they eagerly flung their arms around each other for a photograph. Despite the adversity and the enormous losses they have both endured it was easy to see the little boys who became friends 6 decades ago. All they want is to go home once more. As we talk it emerges that both have lost at least one of their 11 children since the start of the violence. Both tales so sad, so horrific that I can’t tell you here what happened, but the grief is painful to listen to and to share.

One of Feras’ 11 children, his 30 year old daughter and her 5 children also fled with him. She extended a warm and open friendship to us that overwhelmed me. Animated and engaging like her father, she spoke with passion and a sparkling wit about their present. She is surrounded by friends both old and new. Her friends dropped in over the afternoon and the warmth and closeness of their relationships and the support they offer to each other was obvious and heartening. They nudged each other and whispered and giggled at their own audacity. They see each other very day. I was so glad for them. In the worst of times they have formed a circle of the best of friends. They see the positives in their situation. It is hard but the children are happy in school and the local population is welcoming and kind. There is one enormous sadness in their lives. Their father is not there. He left 2 months ago to seek treatment for cancer. Treatment he cannot afford in Jordan. They don’t know when they will see him again. They keep in touch via Whatsapp on their phone. The only possessions Kawther has are her handbag and her phone.

As we start to make our goodbyes, there is more giggling and more children race in. More photos are taken and admired. One boy asks if he can have his photo taken with me. Quickly, 2 of his siblings squeeze into the shot and embrace me. My smile is huge. The gifts I have received today leave me humbled and uplifted.

As we start to make our goodbyes, there is more giggling and more children race in. More photos are taken and admired. One boy asks if he can have his photo taken with me. Quickly, 2 of his siblings squeeze into the shot and embrace me. My smile is huge. The gifts I have received today leave me humbled and uplifted.

Day Three and our destination was Azraq Refugee Camp – 2 hours drive east of Amman. Chatting to the families yesterdy we had found that no one can afford to buy fruit so we were determined to stop and buy some treats for the children we would be meeting (as well as copious piles of Haribo too!). Not far into our journey we stop at a little roadside shop. A young boy stood by the highway waving a silver tray to let drivers know there is a snack stop here.

We bought a selection of fruit and a crate of oranges. As everywhere in Amman a couple of the people working there came over to chat and find out what we were doing. We hit the road again only to immediately pause as we took in what we were reading on the roadsigns.

We bought a selection of fruit and a crate of oranges. As everywhere in Amman a couple of the people working there came over to chat and find out what we were doing. We hit the road again only to immediately pause as we took in what we were reading on the roadsigns.

Our proximity to troubled borders was underlined when a little while later these guys drove along side us for a short while

I have never been in the Middle East before and the desert surprised me. Endless miles of stoney ground, only broken by groups of Bedouin, gypsies and camels on the skyline. That and the never ending convoy of oil trucks from Saudi and Iraq.

There is no adequate way to describe the feeling when you arrive at a refugee camp. You may think you have seen it on TV, read about it in the press and know what to expect. Believe me, you don’t. There can be no better way to suddenly and overwhelmingly visualise and understand the mass migration that is currently under way. Azraq is a small camp. It houses, at present, only around 7% of those displaced from Syria alone, yet the tightly packed shelters stretch from horizon to horizon. There is a population far in excess of my native Isle of Skye packed into an area that I can see from my living room window.

The camp is neat and laid out in “villages” I am repeatedly told by our security escort that here they have learned the mistakes from the construction at Za’atri camp. We’ve been told that there is a hospital at the camp and we stop outside briefly before going to see one of the most surprising and wonderful aspects of camp life. It’s important to remember that all of life’s ups and downs carry on even amidst fleeing from war and living this strange new life in a foreign country. People are born, people die. Children get sick. In the first hour at the camp we meet a lady carrying her 2 day old baby and we share a quiet moment with a lady who has recently lost her mother.

The night before our visit to Azraq we share dinner in Amman with Leena from the World Vision team in Jordan. She cannot wait to tell us about an amazing project to bring football to the refugee children of Azraq camp. World Vision has built 2 artifical pitches in the desert and with the help of coaches from the Premier League 40 volunteer coaches have been trained and a keenly contested league established. As we drive up to the first pitch we can see that a match is under way. The pitches are in constant use – particularly in this week off school – but also during the school week when 2 hour daily training sessions are allocated to differing age groups. The tiniest boys were happily hanging out watching their big brothers play. It was an inspired project – it has clearly brought so much to so many in the camp.

We drove to one of the villages to meet a family in their shelter compound. As we climbed out of our van we were surrounded by a gaggle of children who wanted to say hello and try out their English. We handed out oranges to eagerly outstretched hands.

We were taken to the home of one of the star football players. We ducked down a “street” where each family has screened their compoud with sheeting and food sacks.

His family welcomed us in and served us the most astonishingly strong coffee and endless glasses of hot sweet tea. This family had travelled from Damascus where the father was a lecturer and social worker, Hannah, his wife and he were so proud of their children. Their 13 year old daughter studies constantly and wants, she told us, to be a lawyer. Their son Ahmed, despite his football prowess, wants to be an engineer so he can “rebuild Syria”. Each family (of more than 7) occupies two shelters. The shelters are corrugated iron sheds with insulation held into the roof spaces by UNHCR food bags. The families have an open hand in how they allocate their shelters. Most have a guest and sleeping space in one shelter and a cooking and living space in the other. This family were so open and happy to show us their rudimentary kitchen. I noted the tea towel hanging by the sink bearing the Turkish words ” I love you” and wondered about the story that brought it into their home in the desert.

As we were leaving Ahmed nudged my arm and asked “have you seen these?” He wanted to show me his football boots. His one possesion.

As we travel between the villages in the camp to meet another family I reflect that it is neat, it is organised, it is somewhat soul-less. The only splashes of colour come from the washing strung out between the shelters.And the mosque. Otherwise there is nothing but the grey white of the shelters and the dirt that turns to caking mud at the lightest rain.

We meet another family from Daraa. Their Mum is making macaroni for lunch when we arrive and their oldest son serves coffee to this influx of visitors. The adults are wary of photography. There is a deep seated fear amongst many refugees of photography, being identified, form filling and the paraphenalia of bureaucracy that goes from everyday to terror when you have lived through the horror and violence and threat that all of these refugees have seen. Some still have family in Syria and they fear for them.

As we chat the father tells us that there are 3 things that his family loves. Syria, education and drawing. It is difficult to study sometimes as there is no electricity in the evenings. Sitting quietly beside him are his 7 and 8 year old daughters. They are very shy and peek at us from beside the safety of their Dad. “Do they like to draw ?” we ask. Stephanie pulls paper and a packet of felt tip pens from her bag and slides them over to the girls. Their demeanour changes instantly and they leap towards the pens and paper and opening the packet they start discussing what to draw. After that they are lost to us, heads bent together drawing, colouring, working together. We carry on chatting with their parents.

From under the cushioned pads we are kneeling on the father produces their paperwork and school certificates. This happens time and again with the families we meet. They left with nothing. They became stateless. But before they left they took what was valuable to them, the education certificates. They want to be able to show that they are clever, that they have so much to give. Nothing makes me feel more helpless on this trip than looking at these certificates that are eagerly handed to me. I can see the potential, I can feel the desire to learn and to re-build.

The girls finish their drawing and we admire it. We smile and tell them what lovely colours they have chosen. They blush. Then, heartbreakingly, they slide the pens back to us. “No” we exclaim “they’re for you” and then we all look away and blink rapidly before turning to smile at each other once more.

Our time in Azraq is nearly over. There is a strict curfew for visitors to leave the camp. The security guard takes us to the “hill” that overlooks the camp and it is there that I shoot the frame that has caught the imagination of my visit to Azraq. As I overlook the camp a group of young girls comes scampering up towards me to say hello. I ask if I can take their photo and for a brief moment they pause. I capture them, backlit against the endless sprawl of their new world. Most people on seeing this shot for the first time believe that they are looking at a group of children on the beach as waves roll in behind them. These children could not be further from the sea or a day at the beach.

It’s quiet in the van as we head back to Amman. There’s so much to think about. So much to remember. We gaze silently at Amman as the sun sets over this generous country.

I visited Jordan with the charity World Vision. They have launched a campaign Barefoot Coatless that asks you to go barefoot and coatless for a day on 10th February and to experience a little of the discomfort that these refugees and those across Europe face during winter. Please do click on the link and give if you can.

[…] eloping on the Isle of Skye instead of having a big wedding. I found this photographer because she went to Jordan with World Vision this month as part of a campaign to bring awareness to refugees in winter, asking the rest of us to go […]